Evolving Palestinianism: A Vital Task for the Next Phase

Israel, as the self-styled ethnic state of the Jews, leverages the continuing dominance of the Biblical account as a foundational para-history of the West, and much of the World, to create and maintain the legitimacy of the usurpation of Palestine. Even where the Bible story is no longer read as categorical fact, the acceptance of a linear history linking the contemporary Jewish population, imagined in anthropomorphic unitary terms, with some form of the Biblically reported events remains the dominant reality in discussions about Palestine. Many proponents of Palestinian rights would thus note that the Palestinians have lived “for centuries” in their towns and villages, and that Jewish Israelis ought therefore not displace them in reclaiming the land. The double fallacy of such an argument is in the reality that Palestinians and their ancestors have lived on their lands since times immemorial, not mere centuries, while the Jewish Israelis, beyond overwhelmingly, trace their ancestries to other lands altogether, and are in no way “reclaiming” Palestine.

There is indeed an imbalance in presentation; maintained and enhanced continuously by deliberate narrative crafting on the part of the pro-Israel camp, with still inadequate counter-presentation on the Palestinian side. With the over-saturation in information currently expanding globally, this imbalance requires pro-active actions with clear elements to rectify the falsification of history, used in the further dispossession of the Palestinians.

Past and present assaults on Palestinian identity notwithstanding, it was not a deficiency that the Palestinians had not had to formulate a distinct “protected” collective identity prior to the advent of the colonial-settler project. Well into the twentieth century, Palestinians, as well as most others in their environment, lived their cultural and social identity in the form of a matrix of continuities. From local belonging through communal and family ties, extending to regional, national, linguistic, religious, imperial, and historical dimensions, identity was fluid yet confirmed, not needing categorical assertions, while remaining confident in its reality—singular or plural, as a function of negotiated contexts. While tensions and distinctions in identity existed, a new order of magnitude in contestation emerged in the 19th century, with nationalisms spreading from Europe into the Ottoman domain, bringing proclaimed essential truths along obfuscated uncertainties. The Ottoman socio-cultural scene thus experienced further stress with the coalescence of expressions of Pan-Islamism, Ottomanism, and competing nationalisms: Turanic, Arab, and others.

It is, however, a distinctly European import, Zionism as an openly colonial project, together with the geographic restrictions imposed by the Mandate system, that thrust Palestinian society into pursuing more sharply defined identity formulations. Over the course of the century-long colonial-settler project openly seeking to erase and supplant the Palestinians, the adopted formulations of Palestinan identity have oscillated in a search for ones best suited to secure presence and confirm rights. The Palestinian collective was thus variously advanced as a Muslim-Christian commonwealth, a Syrian and/or Arab local variant, an expression of an internationalist anti-imperialist Third World revolutionary movement, before coalescing into a consciously Palestinian isolate. The inadequacy of the “universal values” claim in addressing Palestinian injustice enhanced, in many settings, a reversion to religion as a moral frame of reference.

This dual development, towards a distinct “Palestinianism” and a more transcending Islamism, redrew the lines of demarcation with the Israeli/Zionist/Jewish narrative implicitly, and at times explicitly, recasting Palestinians as the descendants of the Canaanites (and/or the Philistines), the original inhabitants preceding any Jewish claim to sovereignty in the mythical First and historical Second Temple eras. The Islamist input redefined the conflict as both millennial and millenarian, invoking presumed ancestral enmity between “Muslims” and “Jews”, reframing the ongoing conflict as religiously sanctioned and prophesied.

In fact, both arguments, “the Palestinians as Canaanites” and “the Muslim-Jewish conflict as pre-ordained,” are detrimental to the Palestinian cause, and have in fact been leveraged against it. The Zionist reductionist stance usually dismisses any claim of an indigenous Palestinian presence, defining the population as “Arab”—sourced in “Arabia” or recent migrations from adjacent territories benefiting from the Jewish “rebirth” in “Eretz Yisrael”. However, association with Canaanites and Philistines suits narratives promoted in Western religious or post-religious milieux, within which the current crisis is seen as an age-old conflict granting “Israel” divine and historical title to the land and tenacity to claim it.

Some Palestinian revisionist arguments, based on empirical and critical scholarship, have questioned the pro-Israel historical narrative by highlighting the absence of archaeological evidence supporting it. While anchored in sound research, they have faced fierce rhetorical rebuttals, including ironic accusations of seeking to “erase Jewish history”. Current pro-Israel narrative shaping addresses historical lacunae by colonizing claimed and unclaimed histories (e.g., using Greek and Roman references to Phoenician and Punic elements as stand-ins for Judaic presence) and emphasizing marginal genetic links between Jewish populations and Middle Eastern ancestry, often through questionable statistical methods.

To avoid arcane polemics, it may be more useful not to seek to deconstruct the precarious, faulty pro-Israel narrative, but instead to revisit and revise the Palestinian self-assertion tactics and presentations.

The “Islamicization of knowledge” project has suffered trials and tribulations, often falling into pseudoscience. Where its contributes value, however, is in challenging the dominance of the Biblical foundational para-history. This in not through denying the religious epistemological prerogative of Christian, Jewish, or Western post-believers to regard the Biblical narrative as truth, but by presenting the parallel Islamic alternative, in which Biblical prophets are Muslim prophets, and Biblical para-history yields to Islamic para-history. If Israel claims Jerusalem has been the “Jewish” capital for millennia, the same can be asserted for the Holy Land as a Muslim land for even longer.

The purpose of this Muslim assertion is to expose the non-binding nature of what is presented today as dogma. It serves as a remedial action. A reconsidered Palestinianism, on the other hand, can provide pro-active assertions.

Palestinianism ought to free itself from the trap of validating the Zionist narrative by contesting the Jewish exclusivity to a “Promised Land” and debating an age-long “Jew and Gentile” confrontation. Instead, for episodes historically ascertained (the Judean dynasties of the Second Temple and the Jewish, and Samaritan, revolts), Palestinianism ought to claim its own heritage: these episodes are the history, revolts, and resistance of the ancestors of today’s Palestinians, while the current Israeli-Zionist state represents a functional heir to foreign imperial oppressors.

The ancestors of today’s Palestinians in Roman and Byzantine times resisted oppression and suffered defeat multiple times. Many espoused faiths that retroactively are labeled Jewish, later majority converted to Christianity and then to Islam. No recorded Roman expulsion of Jews from Palestine exists. The ancestors of Palestinians, including Jewish and other faiths, never left their lands. Jewish communities, some migrants and some converts, were established elsewhere—there lies some of the ancestors of those who may have continued to be Jewish, cherished an imagined Jerusalem, and some, many centuries later, were subsumed into Zionism. A vocal assertion is to be absorbed into the Palestinian consciousness that the Palestinian people facing the wrath of the US-Israeli “empire” today traces a significant part of their ancestry to the Jewish resistance against the Romans, a historical episode recycled against them by current occupiers.

This re-direction is neither polemical nor redefining Palestinian identity; it corrects an omission, and rejects the occupation of a historical episode by the project of dispossession. For the pro-Israel narrative, this may pose existential challenges or, less likely, opportunities for affinity and reconsideration if accepted earnestly. Regardless, Palestinian identity faces ongoing erosion through Israeli narrative crafting, making rethinking identity elements an act of resistance.

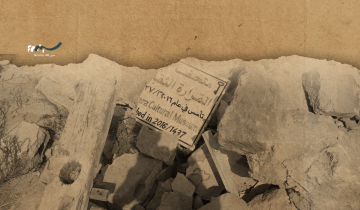

Photo Credit: Tareq Bakri.

Dr. Hassan Mneimneh

Principal at Middle East Alternatives in Washington, DC.