Memorializations from Below

It was 15 May 2024. On a college campus in southern California, a student protest encampment was in its second week of occupying a school lawn to protest the Israeli government’s brutal assault on Gaza. It was one of the hundreds of college campuses across the country that took action as part of the largest nationally coordinated student activist effort in decades. On this particular day, the student protesters took over a building at the University of California campus in the city of Irvine. They sang chants while beating drums and hoisting protest signs. As they took control of the building, they hung a banner renaming it “Alex Odeh Hall.”

Similarly, at Columbia University student activists set up “Hind’s Hall” to honor the little girl Israeli soldiers murdered in Gaza. Hind Rajab’s name is widely known among Palestine solidarity activists. Alex Odeh, however, is not. Odeh was a Palestinian-American activist who was murdered in 1985 by a bomb that went off as he opened his office door in Santa Ana, CA, another Orange County city just miles from Irvine. Odeh’s killers, like Hind’s, have not been brought to justice, benefitting from the US-Israeli system of impunity that has made Palestinian lives expendable.

Both Hind’s Hall and Alex Odeh Hall were temporary re-namings, thus fleeting, informal, and only signified by activist banners. Once police cleared the protesters, the official names returned to primary display. Memorialization through official naming practices or monuments, always reflect some dimensions of power. Permanent material articulations through statues, plaques and building names reflect power’s norms about what or who is to be publicly valued. But activists continue to thrive and resist by redefining these symbols, reclaiming space, and working locally to found their own commemorations, creating resilience through remembrance.

In late 2023, the Israeli occupation forces went on a rampage in Ramallah. Its bulldozers removed public images of the long-deceased icon of Palestinian national aspirations, Yasser Arafat. Any monument to Palestinian resistance also came down. The six-meter bronze statue of Nelson Mandela in Ramallah’s Mandela Square, a gift from the city of Johannesburg in 2016, seemed to survive the onslaught. Israel was content to smash Palestinian memorializations without risking international uproar. Mandela was, in a way, too powerful a symbol to erase. In January 2024, Palestinians gathered at the square to show appreciation for South Africa filing the case against Israel for violations of international law in Gaza before the International Court of Justice.

Elsewhere, activists re-define statues though artistic action. They use graffiti messages to turn symbols of power into symbols of critique. Palestine Action once removed and hid a statue of Zionist leader Chaim Weizmann in the UK. Student protesters placed a keffiyeh around the neck of George Washington in Washington, DC, which garnered an angry response from members of Congress. These acts transform established power icons into platforms for Palestinian resilience and visibility.

When it comes to official memorializations, Palestinians are so often relegated to rebellious tactics: disrupting, remixing, and redefining, as outsiders even in their own homeland. This is what makes Alex Odeh exceptional. While Alex Odeh Hall was brought down quickly, since 1994 there has been a statue of him in front of the Santa Ana public library. Designed and sculpted by the Algerian-American artist Khalil Bendib, the statue portrays Odeh in a thawb, holding a dove in one hand and a book in another, reflecting his pursuit of peace and commitment to learning; qualities he sustained despite the violence aimed at silencing voices like his.

Odeh was an author and teacher at local universities while leading the west coast chapters of the American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee.

Militant Zionists in the United States were angered that the city of Santa Ana allowed a statue of Odeh to be erected. One of its fiercest critics was Irv Rubin, chairman of the Jewish Defense League (JDL), founded by Meir Kahane. During the event dedicating the statue, Rubin jeered at the attendees, including Odeh’s family. Helena, Odeh’s eldest daughter, recounted: “we were standing behind the podium … he (Rubin) stood up in the audience, and I'll never forget his words … ‘I shed no tears for Alex Odeh. He deserved to die.’”

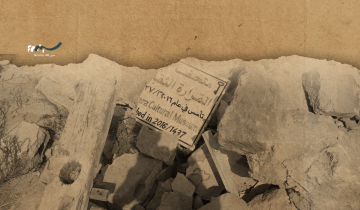

Then, in September 1996 and again in February 1997, vandals smeared the statue with red paint strewn across the statue’s neck, symbolizing a throat-slitting; an attempt to kill Alex again, posthumously. Bendib likened this to seeking to erase his memory. The JDL treated Alex’s presence in public memory as an intolerable expression of resilience and identity. Surely, they wished the statue was in the West Bank where it could be destroyed outright.

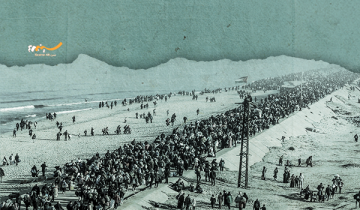

Santa Ana, the city in which Alex was killed, is not like other cities in conservative Orange County. It is a largely Latino city with progressive politics and in recent years has been a central place for immigrant rights demonstrations, including the Trump administration’s ICE raids the past few months. Marchers passing by the statue placed pro-immigration placards on Odeh’s lap, symbolically linking their struggles. Odeh himself was an immigrant, though not by choice. Odeh was studying in Cairo during the 1967 war. Israel prevented him from returning to his hometown Jifna in the West Bank. He was one of the hundreds of thousands of Palestinians displaced during Al Naksa.

Alex Odeh remains the only Palestinian memorialized in statue form in the United States, thanks to the advocacy of his community and the unique local context of Santa Ana. As supporters of Israel in western countries wage campaigns to silence, forget and erase Palestinians from public consciousness, those of us in the diaspora must actively work to etch Palestinian history, resilience, and resistance into forms, practices, and places where erasure is no longer inevitable.

Dr. William Lafi Youmans

A media scholar and documentary filmmaker. His work broadly explores questions of transnationalism, power, and communication, with primary research interests in global news, media industries, technology, law and politics. Youmans is the author of Unlikely Audience: Al Jazeera's Struggle in America (Oxford University Press) and has been quoted in numerous publications, including Salon, The Washington Post, Newsweek, Variety, and The New York Times.