Memory Under Fire: Art and Culture Confronting Genocide

As I write these words, a sharp question presses at the edges of my mind: What, truly, is the purpose of art and culture in the face of genocide? What can a poem, a painting, or an archival document possibly do against a ruthless war machine that leaves nothing alive in its wake, against warplanes that erase entire neighborhoods from the map, shatter families, and turn bodies into unrecognizable ash? Perhaps no one holds a definitive answer to these questions, deceptively simple yet unbearably profound. And perhaps neither art nor culture can halt a genocide unfolding before the eyes of the entire world. Yet, even so, they can bear witness, carrying the memory of the survivors and the long arc of their history into the years to come, if survival itself is possible.

Conversely, no genocide occurs without a deep awareness of the power of narrative and memory. Control over the present is never possible without a parallel rewriting of the past; a truth the Israeli cultural apparatus understands all too well. Through institutions, archives, films, and exhibitions, it works to cement the narrative of the “absent Palestinian” and replace it with that of the “settler-fighter”.

In contexts of colonial violence, especially under genocide’s shadow, culture is never a peripheral casualty destroyed incidentally or at random. It stands at the very heart of the genocidal project, serving as a structural instrument of domination. As Milan Kundera observed, the erasure of collective memory is one of the most profound pathways to annihilating a people, carried out not only through killing, but also by dismantling everything that gives a people its name, history, language, and narrative. In Gaza, where war’s machinery strikes indiscriminately, destruction of bodies is always accompanied by erasure of their symbolic trace. Killing thus becomes a double act: the annihilation of the body on one hand, and the murder of the story that could have been told on the other.

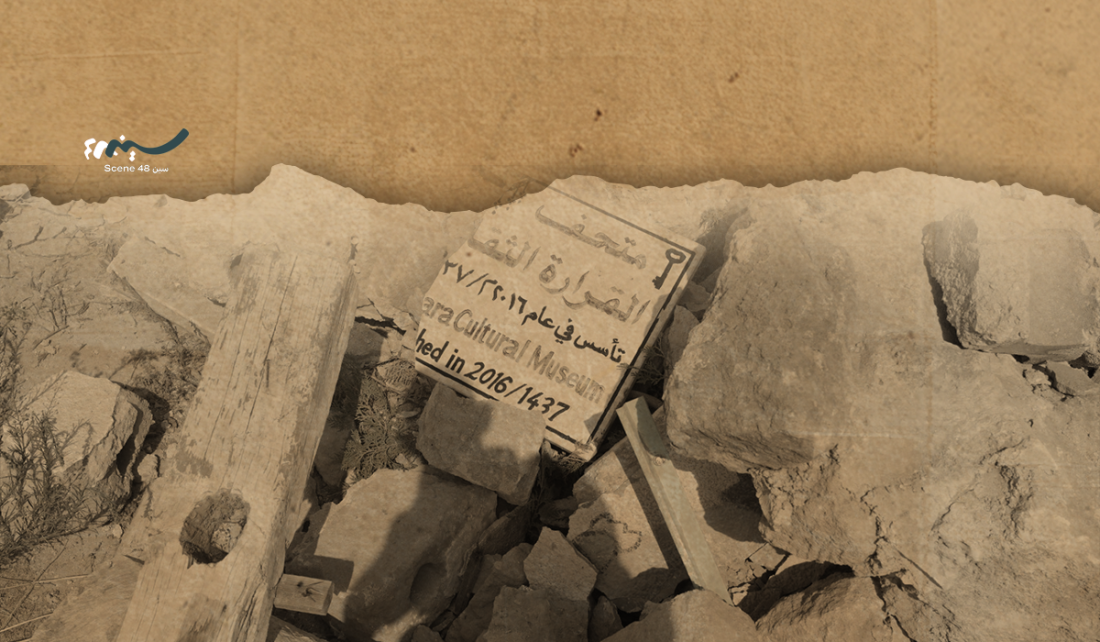

As part of this war on existence itself, Israeli airstrikes have destroyed hundreds of archaeological and historical sites, public and institutional libraries, cultural centers, museums, heritage buildings, and entire neighborhoods once vital to cultural life. More than a hundred cultural workers, including artists, writers, heritage curators, and intellectuals, have been martyred. Each loss is a rupture in the Palestinian collective narrative, erasing a fragment of memory and consciousness, exactly as genocidal projects intend.

What has unfolded in Gaza since 7 October 2023, cannot be measured solely by the number of martyrs, the missing, or the demolished buildings. It must also be reckoned in terms of what this loss, this destruction, means for the city’s symbolic fabric. The targeting of universities, museums, publishing houses, libraries, theaters, and cultural centers can only be read as a systematic effort to erase the Palestinian altogether and extinguish any hope of return.

The danger of this erasure is that it leaves behind no documents, no witnesses, no possibility of re-narrating the lost. Surviving artworks, photographs, posters, and personal archives salvaged from the rubble become far more than aesthetic artifacts: they stand as documentary evidence of an entire people’s existence, fragile visual traces bearing witness to their presence.

Philosopher Paul Ricœur offers a lens for understanding the link between memory and identity. Memory, he argues, is not merely an individual recollection but a narrative structure formed over time, continually reshaping the collective self. Identity is constituted through remembering, yet remains perpetually threatened by erasure, distortion, and enforced oblivion, making archives, testimonies, and material traces indispensable for preserving what Ricœur calls “continuity over time”.

In Gaza, when archives become ash, when books burn to warm exhausted bodies, when artists set fire to their own works for cooking flames, and when museums and universities are bombed, what remains are symbolic voids where sites of memory once stood. These absences are deliberate: hollowing out of an entire cultural landscape, the removal of spaces where a people’s memory might anchor itself.

By contrast, Israeli memory is never spontaneous or haphazard. It is meticulously produced and curated through vast institutional and cultural infrastructures. The Zionist state places memory at the very heart of its settler-colonial project, reconfiguring the past to serve present politics and deploying narrative and visual tools to construct a “collective memory.” As Eyal Weizman notes in his analysis of Israeli architecture and mapping, what is built reshapes not only terrain but political consciousness, obliterating possibilities of Palestinian remembrance.

While Palestinian memory fights to survive and be told, Israeli memory is designed in sovereign, closed rooms, reinforced through dense visual and material production that not only preserves its own version of history but actively excludes any authentic, dissenting narratives.

Thus, the Palestinian fight for memory is not only resistance to oblivion or erasure; it confronts a colonial narrative apparatus reshaping time, space, and events to serve its own agenda. When the past is erased, the present becomes fragile, and a people are stripped of their fundamental right: to imagine, rebuild, and shape their future.

In this context, Palestinian art and cultural assume exceptional urgency. Art transcends mere aesthetic or symbolic expression; it becomes survival, and an unyielding testimony. Beyond documenting the past, it creates new spaces for memory and enacts a deliberate resistance against forgetting. When archives burn and voices are silenced, art remains an act of defiance and a repository of memory.

As Edward Said famously reminded us, cultural resistance, through literature, art, and collective memory, is one of the final bastions for a besieged people, a last stronghold where identity is fiercely defended, even in the shadow of annihilation.

Photo: The bombed Al-Qarara Museum in Khan Younis, Gaza. Credit: Mayasem Association for Culture and Arts.

Sura Abualrob

The Media and Communications Coordinator at the Palestinian Museum, and is a Master’s student in Integrated Digital Media at the Arab American University. Her research interests focus on the intersections of media, memory, and narratives.