What Comes Next

I was meant to be one of those who would forget. I was raised in forgetfulness, as in a dark, obscuring, evergreen forest—the kind that burns quick under the siege of forceful winds on a nice hot day.

My father wanted to forget. To forget the village of his childhood. To forget fleeing Jerusalem at the age of eighteen with Nakba’s beginning. To forget his time in an army, his time commuting to neighboring Arab countries for jobs, sending money back to his newly formed family. To forget the wife and children he left in Beirut after ’67, making a new life for himself in North America (they went on to Australia). To forget to teach me, the first child of a second marriage, his native language. To forget to tell me that we are Palestinian, that there is a place we come from, that displacement is never a chosen state. Each branching of forgetfulness slowly covering a ruin.

I was meant to be one of those who would be forgotten. A rumor, an oddity, a dilution, an embarrassment, a defeat. But somehow, through some sense of refusal and indignance, and through some mysterious grace, I remember, and there are some who remember me.

It’s difficult to tell the story when one must expose a father’s silences, shaped by exile’s violence, to reveal a family’s collective persistence – that spark of persistence kept burning by women like my bint al-‘amma (the cousin), who stayed on the land and never forgot.

But it might be the best way to honor that persistence – to allow it to seed a flame against the backdrop of darkness that would like to extinguish it.

So, when I dare dream about the future of Palestine, it comes as a searing, penetrating light, which burns through dark branches of separation, division, and alienation.

Because we all know who profits from those forests of forgetfulness. We know who planted them to separate us.

I think of how the country my father settled in was as happy to absorb the forms of capital he brought—cultural, financial, labor—as it was invested in forgetting the causes of his displacement and its own complicity, offering class and race advantage in return for his forgetfulness. That absorption separates.

I think of those whose memories have petrified, static and structured and wooden, infected by an occupier’s logic, saying things like: “There were no women like you in Palestine; there are more important things to worry about.” That deflection divides.

I think of the lack of language, the fear of language, the alienation of language, and bint al-‘amma says: “Ma‘alish.”

“When they say you don’t have the right name, learn to say: ‘Ma‘alish’.

When you feel lost, lacking Arabic, while you learn, pronounce it just like this: ‘Ma‘alish’.

When you fear your existence is but the ash of Nakba, clench your teeth and breathe a blade beneath your breath: ‘Ma‘alish.’

And remember the Ma‘alish of others, of Wael al-Dahdouh, his wife and children slaughtered, his response: ‘Ma‘alishhhhh’.”

How powerful a remedy to forgetfulness is this defiant “never mind”. My elder cousin’s kinship of acceptance is a shield and not surrender. A shameless declaration: no matter what! We belong, no matter what, we keep on.

It prompts me to remember the pine tree, sacred to the Indigenous peoples where I grew up, the image of which was captured, repurposed in ‘charitable’ settler-colonial delusions, tools of erasure to serve the occupation’s brittle performance of indigeneity.

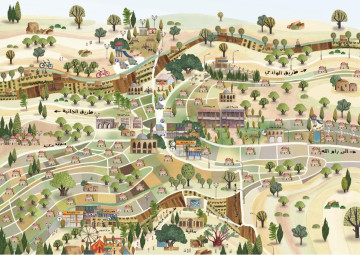

I dream of what those pines obscure, the attempted oblivion of orchards and villages, ‘Imwas, Bayt Nuba, Yalu.

I see a searing light that metabolizes oblivion instead of succumbing, that liberates what has been captured through ravaging fire.

I witness the fragility of institutionalized delusion, resin-thick, flammable, torched quickly under the siege of forceful winds on a nice hot day.

I think of how many meals must be cooked together but not eaten together, each one on her own side of the video screen, one directing the other not to forget—do not forget to fry the okra first! How many times must the embroidery be undone? How much longer will Gaza’s cousins starve and fight while we cook and cry? How many times will their resolve leave us wordless and bewildered? How much longer can we wonder what comes next?

How many of us were meant to forget, raised in forgetfulness, as in a dark, obscuring, evergreen forest. How many were meant to become rumor, unfamiliar, and defeat.

And what will be when these rumors return—those meant to be forgotten—and grow hard roots that crack checkpoint concrete? When climates, natural and political, heat and shift and blaze—not through appeal and concession, but hard-won defiance?

I believe in liberation, not just various forms of absorption, and I believe in love. There are people in Palestine whom I love, and there are people who love me in Palestine. It’s a hard, burning, transformative love, and what will be found in the embers at the ground of the forest will not be what was there before. And in that searing light, born through Gaza’s steadfast nights, we struggle for what comes next.

Photo: Cooking with bint al-‘amma, each one on her own side of the video screen. Photo by author, 2024.

Crina Saad

A professor of literature living on the unceded lands of the Kanien’kehá:ka Nation (Montreal, Canada).