Archives Under Fire: Resisting Erasure Amid Genocide

The genocide in Gaza is the culmination of a century-long Zionist settler-colonial project aimed at erasing Palestinians not only physically but also historically and politically. The bombs, the starvation, the forced displacement, and the destruction of entire neighborhoods are not isolated acts of war; they are instruments of a coherent strategy of erasure.

As settler-colonial theories explain, Patrick Wolfe states: “invasion is a structure, not an event.”[1] The aim is not only to seize land but to remove the indigenous people—physically and symbolically—from history itself. That means erasing not only lives, but also archives, narratives, and cultural records that testify to prior existence. For Palestinians, this has meant a sustained attack on the material and documentary evidence of their presence: the proof that they belonged here before the settler arrived, and that their dispossession is a crime.

In this context, the recent rescue of the UNRWA refugee archives from Gaza carries profound political meaning: it is both an act of historical preservation and an act of resistance.

A Mission Amid Genocide

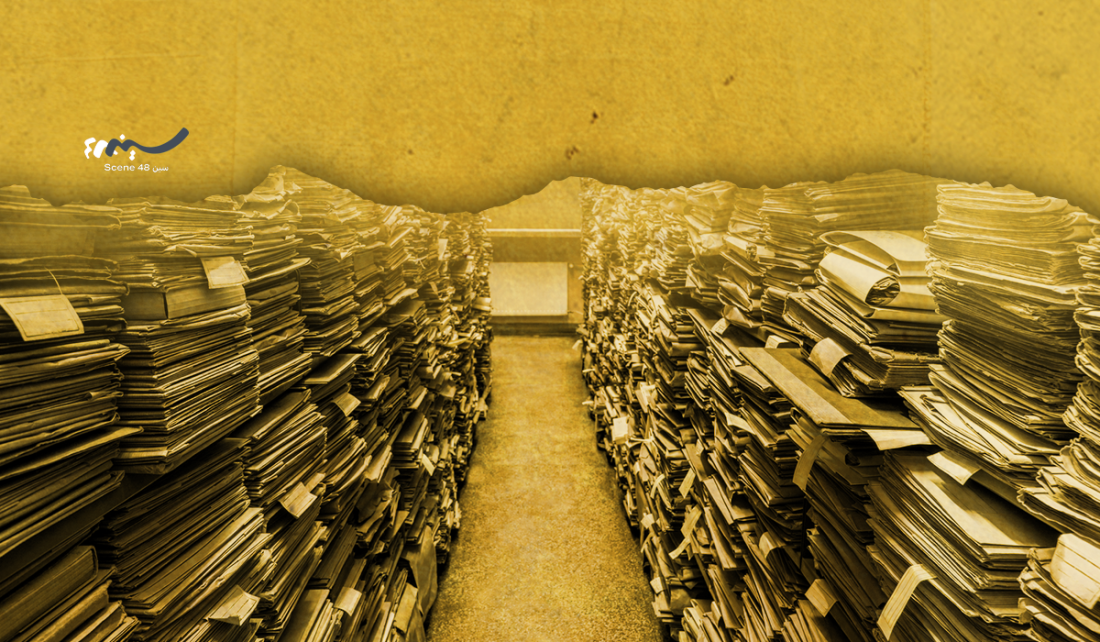

According to an investigation published in July 2025 in Le Monde, in October 2023, just days after Israel began its war on Gaza, UNRWA’s Gaza City headquarters came under evacuation orders. Among the staff was a Palestinian manager who knew that inside the building were the family registration cards of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians displaced during the 1948 Nakba—many not yet digitized. These were not mere bureaucratic files. They recorded names, birthplaces, and histories. They are legal proof of refugee status under international law, genealogical links across generations, and an irrefutable challenge to the Zionist denial of the Nakba.

Before the Israeli ground invasion, small UNRWA teams risked their lives to re-enter the bombarded Gaza City’s Rimal neighborhood, loading the archives onto trucks and moving them south to Rafah. In March 2024, an Israeli airstrike on the Rafah warehouse killed a staff member and injured others. The papers survived; barely.

With the border sealed, Egypt refused to let the archives out without Israeli consent. In response, for months, international UNRWA staff smuggled small batches hidden in their luggage. From Sinai, Jordanian aid flights carried them to Amman, where UNRWA staff digitized and preserved them. In April 2024, as Israeli tanks moved into Rafah, the last batch arrived in Jordan.

Not all records were saved. Many digitized copies of Ottoman and British Mandate-era deeds, and unknown portions of Gaza’s photographic archives, remain trapped (or lost) inside the Strip.

Erasure as Colonial Practice

The targeting of Palestinian archives is not new; it is fundamental to the Zionist project. In 1948, Zionist forces looted the photographic collections of Khalil Raad and seized municipal, waqf and Church records from depopulated cities. In 1982, during Israel’s invasion of Lebanon, the PLO Research Centre’s library in Beirut (a repository of Palestinian history and liberation thought) was looted. In Jerusalem, Israel has confiscated Ottoman-era land records to weaken Palestinian property claims.

This is settler-colonialism’s archive war: the deliberate destruction or theft of records to render a “people without a history,”[2] as Eric Wolf put it. Archives become another battlefield in the settler-colonial logic of elimination.

In this way, the genocide in Gaza and the assault on Palestinian memory are inseparable. The first removes the living; the second removes the record that they ever lived. Both are necessary for the settler to claim permanence. This is why Israel is going out against the UNRWA.

UNRWA is not simply a humanitarian agency; it is also the custodian of the Palestinian refugee record. Its very existence is a reminder that the refugee issue is unresolved and that the right of return remains alive. This is precisely why Israel has intensified efforts to dismantle the agency, accusing it of “terror ties,” closing its offices in Jerusalem, its schools, and lobbying donor states to cut funding. Eliminating UNRWA would mean erasing the primary institutional archive of Palestinian displacement, weakening the infrastructure of memory and claim-making.

Memory as Resistance

For Palestinians and, I assume, for other indigenous people, memory is not nostalgia; it is a form of political existence. The preservation of archives is an act of resistance because it affirms continuity across generations and prevents the settler from sealing the historical record. It allows Palestinians to assert, in legal forums and cultural narratives alike: We were here. We remain here. We will return.

Settler-colonial projects fear this continuity. They know that even if they succeed militarily, the survival of the historical record undermines their legitimacy. That is why the rescue of the Gaza archives in the middle of a genocide is not merely an administrative achievement; it is a direct challenge to the Zionist project’s logic of elimination.

The Responsibility of the Present

As Gaza burns, the West Bank is colonized, Palestinians in Israel face repression, and solidarity movements worldwide are criminalized, the rescue of these archives underscores a central truth: anti-colonial struggle is also a struggle over memory. The destruction of archives is an act of epistemicide: the killing of knowledge systems. Preserving them is the refusal to vanish.

The UNRWA archives now in Amman are more than paper. They are proof of life, evidence of crimes, and maps for the future. Protecting them keeps open the possibility of justice; mobilizing them asserts that Palestinian history will not be sealed in an Israeli vault or erased in the rubble of Gaza.

In the long war of elimination, every rescued document is a victory. Every preserved name is a rebuke to the myth of “a land without a people.” Moreover, every act of archival resistance declares what the bombs and bulldozers cannot silence: Palestinians will not be erased.

[1] Patrick Wolfe, “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native,” Journal of Genocide Research 8, no. 4 (2006): 387–409.

[2] Eric R. Wolf, Europe and the People Without History (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982).

Dr. Nijmeh Ali

A political scientist whose work examines resistance, indigenous politics, and settler colonialism, with a particular focus on Palestine and Israel. She is a Global Academy Fellow with the Middle East Studies Association (MESA) and has taught and written widely on decolonial thought and political struggles in the Middle East.