Shukri Who? Naming, Unnaming, and the Politics of Identity

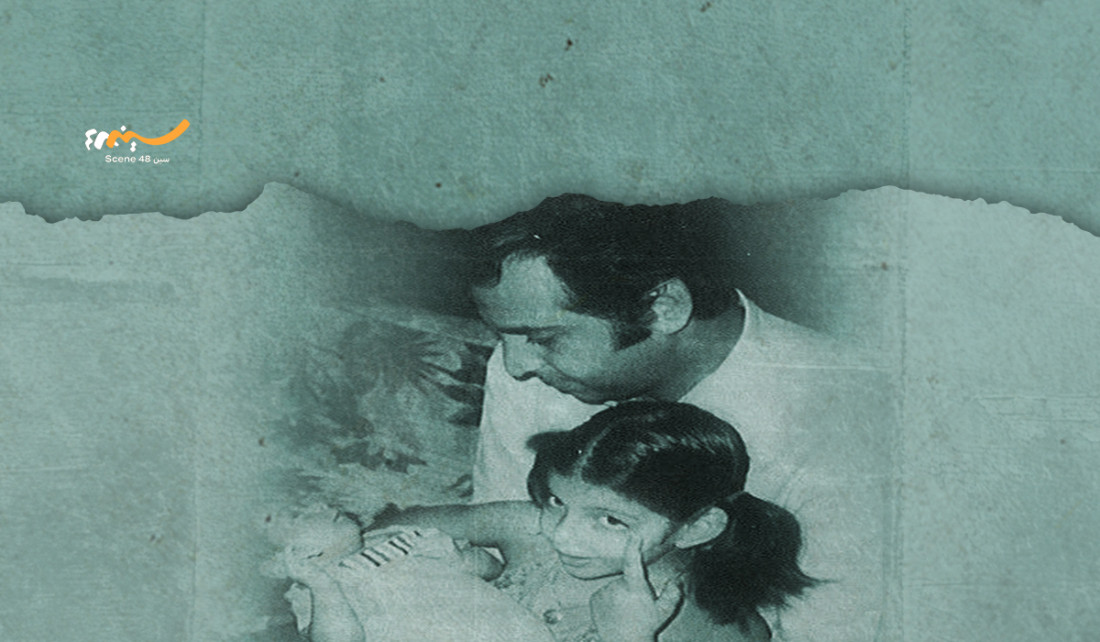

I am half-Palestinian, half-Egyptian, not by choice, but by Nakba. If it weren’t for 1948, my father would never have left Acre. He wouldn’t have traveled to Cairo, wouldn’t have met my mother, wouldn’t have had me.

My father came from a village, not a metropolis. He ate ripe fruit off trees and swam in a spring. To him, it was heaven, all he ever needed from the world. He wasn’t a man of the world, nor a curious traveler taking in other cultures. He was a refugee, moving out of necessity. A man boomeranging between places just to survive.

I was born with a Lebanese passport, because that’s where my paternal family relocated in 1948. Though my mother is Egyptian, I was granted Egyptian citizenship in my thirties. Until then, I had to renew my Egyptian residency every few years and pay school tuition at the foreigner’s rate. Still, I was told Egypt was my home. Never mind that my father wasn’t living in “my home.”

“Min beit min?” (from whose home are you?) is a common question in Arab culture. When I was asked that growing up, no one in Egypt recognized my last name. “Are you related to Shukri Sarhan?” they’d ask, referring to the Egyptian actor. Never mind that my name isn’t Sarhan, it’s Serhan. The mispronunciation always irked me, but I never corrected it. When people asked, “Where are you from?” my mind scattered.

I am Lebanese, though my accent is Egyptian.

I am Egyptian, though my father is Palestinian.

I am … Palestinian?

This last one always carried the tone of a question.

So when I tell you my name has always felt like a thing of air, I am not trying to be poetic or dramatic. It is true. And when I tell you I’ve always felt most at home in airports or in the air, I have good reason. In the airport, everyone is just passing through. And in the air, no one is home; not even me.

But every so often, something or someone brings me back to earth. A few years ago, before October 7th, I was seated at a friend’s farewell dinner next to a family with a hyphenated identity. They were Libyan-Syrian-Palestinian. I asked the mother which identity they identified with most, and without hesitation, she said, “Palestine.” She then leaned on me and, with a Syrian accent, told me her late husband always said, “We are all Palestinian until Palestine is free.”

That moment crystallized something vital for me. It wasn’t simply about choosing an identity; it was about embracing one that called to me beyond choice. It allowed me to shift the emphasis to what needed me most. To give myself a name, despite erasure. Give the name weight, despite its airiness. Register presence, despite absence. To name it was an act of resistance; and it felt so good.

This shift in self-recognition came with its own set of issues. When my memoir, I Can Imagine It For Us, was released, my bio stated: “Mai Serhan is a Palestinian living in Egypt.” Naturally, this declaration stirred some surprise among my Egyptian friends, lifelong companions who saw me as one of their own. To deal with the conundrum, I called my mother to ask if she was OK with it. Her reply surprised me, but also offered a quiet release. She said, “Your father is Palestinian, then you are Palestinian.” And so it was, ironically, that in the legacy of patriarchy, I found relief.

You might wonder why my mother so quietly surrendered any claim to my lineage, but I think I know why. I grew up saying “we” when Egypt won a football match, stood still when the anthem played in school, and memorized lines of Salah Jahin’s poetry like scripture. Egypt is also a sovereign state, with a permanent population, defined territory, a government, and no missing parts. No one gets arrested for waving its flag. Unlike Palestine, there is no such thing as the Egyptian question. To my mother, my Egyptianness was never in doubt. She understood that this wasn’t about personal identity; it was about identity politics.

So while I owe my friends an explanation, I owe this moment a declaration. Right now, hundreds of thousands of Palestinians have been displaced or blown up at the hands of a genocidal entity. I’ll skip the gruesome details. Hundreds of thousands of other Palestinians beat them to it 75 years ago. If not of alien status, they’ve been assimilated into other cultures, though never completely. The American empire maintains there’ll never be a Palestinian state. Tony Blair has re-emerged from the woodwork to execute the colonial wet dream. A handful of European nations have “recognized” Palestine, never mind it being around for four thousand years. What all this means is: Being Palestinian is no longer a choice, it’s an imperative.

Amid this relentless assault on identity, whether you’re seen as more or less Palestinian, because of your accent, your passport, or your distance from the land, is beside the point. The Palestinian tapestry is vast and varied and beautiful; its strength lies in the intricacy of its weave. To live in translation, to answer to a name that’s often misheard, this, too, is part of the thread. By a design not always visible, it’s made to hold.

Mai Serhan

A writer, editor, translator, and creative writing tutor. She is the author of CAIRO: the undelivered letters (Diwan Publishing, 2025), winner of the 2022 Center for Book Arts Poetry Chapbook Award and I Can Imagine It For Us: A Palestinian Daughter's Memoir (AUC Press, 2025), a finalist for the 2022 Narratively Memoir Prize. She holds an MSt in creative writing from the university of Oxford and has studied at NYU and AUC. She lives in Cairo.