Spatial Resistance

Living and working in al-Naserah provides a distinct take to what it means to have a Falasteni spirit while living under, and being surrounded by, the Zionist settler colonization entity.

It is to worry that any act to seize haq taqreer al-maseer (self-determination) conveys: the collective right to imagine and shape one’s own becoming, which is not an individual right but rather a shared act of imagination, grounded in presence, resistance, and survival.

It means to reweave and reawaken our relationship with what was, and still is being stolen from us, as individuals; communities and people, to recollect our fragments.

|

|---|

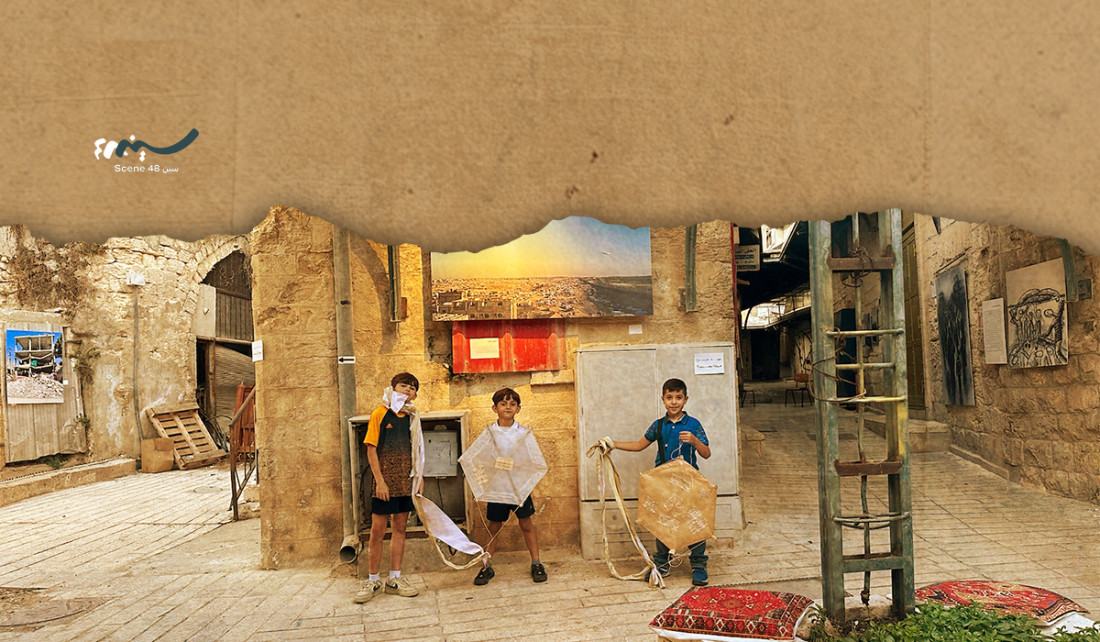

Photo by: Lara Makhoul. A view of the exhibition

What does it mean to preserve Palestinian heritage at risk of erasure within the gaps of uncertainty? How can memory take shelter when heritage homes cannot endure? And how might architectural heritage keep at its center of what people hold most dear is al-beit or al-dar (the home) not only in form, but in meaning? The Palestinian clinging relationship with al-beit is more than a “refuge” and shelter; it is the soul of Palestinians, reflecting values, continuity, and togetherness. It is an enduring symbol of steadfastness and rootedness in the land. When the house is lost, the land is lost.

As a Palestinian architect from al-Naserah city, through my artistic practices I seek to reflect the gaps with our Palestinian roots, confront our deep open wound, by searching to unveil the spirit of my city, which lies in our human heritage, that weaved our city as one cluster. To reidentify our collective identity that was formed in respect to the other; as one holistic cohesive community fabric, who lived from and for al-’ard (the land) and knitted our urban fabric.

|

|---|

Photo by: Lara Makhoul

Thus, this became a responsibility to reclaim what was stolen and seized from us by Israeli settler colonialism: our spaces; memories; and our imaginations to substitute their new fabricated narrative and pure Jewish demography, aiming at eliminating and erasing the Palestinian identity of each Arab city and village.

These same spaces are abandoned today by us, the descendants, who deserted our own heritage, not out of our own will and ignorance but due to hidden and slow forced displacement over 76 years of mental colonization and cultural genocide, resulting in detachment and disconnection with our extended and cumulative cultural heritage and aesthetics; produced by our predecessors, hundreds of years of hard work, love, and creativity. Those spaces keep our memories, give living testimonies of those who lived them, visualizing how we once lived.

|

|---|

Photo by: Lara Makhoul. The artworks are by Yasmin el Dayeh and Jehad Jarbou

Today, the untold stories and unheard sounds of our cities are amplified by the voids of emptiness, due to the absence of those who produced our rich characteristics and resonate through the stones of the abandoned heritage houses, degraded and collapsing.

As we strive to revive the spirit of the place, and reawaken its spatial memory, these spaces expect from us to simply listen, see, and be present in the abandoned spaces, rather than coexisting with violent modern built environment nurtured by the occupier, that we are building with our own hands and living in, unaware of what we will become, and what we are losing.

|

|---|

Photo by: Razan Zoubi Zeidani. The artworks are by Hamada el Kept and the artist Yasmin el Dayeh

Along this journey in search for the spirit of the city, amidst our identity obliteration, ALDAR for research art and architecture, was born in the alleys of the old city of al-Naserah, and in the middle of Gaza genocide; an independent cultural and artistic space established by myself and Daher Zeidani. It’s a resurrection of the unseen and unnoticed Palestinian urban mansions, pure from defilement of the colonizer, accessed and used by the local community. This initiative of architectural rehabilitation becomes an act of reclamation, a tool of resistance towards decolonization. It holds a statement of Palestinian persistence through spatial resistance, memory, and the enduring bond to home: to live is to stay (نحيا فنبقى). Where in the absence of spaces of creativity in Palestinian and Arabic identity, this project endeavors to recapture a space of creative actions inspired and driven by its spatial and urban identity and memory of the place.

|

|---|

The photo shows a reimagining of abandoned places through a lecture/presentation.

The artworks in the background are by the artist “Yara Zahd.”

Falastini spirit is not necessarily in people’s soul, it can be found in the house, the alleys, the shop, something that cannot be easily described. It’s felt and practiced. Not everyone carries it, it’s a state of mind, reflecting strength, courage, and dignity. It belongs to those who endeavor to seize equality, justice, and liberty. Those who advocate the Palestinian cause everywhere, even in their own neighborhoods. We ask ourselves what is the Falastini spirit in art and culture? What is the role of Palestinian artistic spaces in reformulating and reclaiming abandoned places, giving new possibilities in the time of Gaza genocide and while living the colonial condition?

|

|---|

Photo by: Rama Mousa. Artwork by Osama Hussein

To answer this, Aldar collaborated in the global Gaza biennale, where al-Naserah was one of the pavilions curated by Aldar. The pavilion hosted and partnered with 6 out of 60 Palestinian artists living in Gaza, to display their art works in the al-Souk most abandoned alleys. Aldar took this risk to bring the voices of Palestinians under genocide to resist with their peaceful weapon: art. Among 18 pavilions around the world, al-Naserah in al-Souk, al-Mobaydin souk in particular, was the only Arabic-Palestinian pavilion with no fear to confront the occupier’s narrative and insist on this radical and revolutionary act to bring Gaza’s voice through these artists in the open spaces of the al-Souk, despite the policy of silencing dissent. We decided to rise up and scream through this action and bring not only Gaza’s voices, but also ours and al-Souk blatant noise of silence. This project under the title of urban rehabilitation of abandoned spaces brought people closer to their roots, to be present, and use these shops in al-Souk closed for over 30 years of abandonment and neglect, which were reappropriated with a temporary use of art exhibition.

|

|---|

Photo by: Rama Mousa. The artwork “The Scream of Death” by Malaka Abu Odeh

Does every speech of Palestinian cause carry the Falastini spirit? Does every project or program run in the name of Palestinians can be considered as the Falastini spirit? Is it enough to talk Palestinian but not practice as one?

The Gaza Biennale’s Nazareth Pavilion was curated by Razan Zoubi Zeidani, with Daher Zeidani as co-curator, and realized with the work of a volunteer artistic team: Jool Faraj, Lara Makhoul, Razan Haddad, Rama Mousa, Riwa Abbas, and Rua’a Jindawi.

The Photograph shown in the background of the article’s image is by the Gazan artist Jehad Jarbou.

Razan Zoubi Zeidani

A Palestinian architect, artist, and curator from Nazareth, born to Nakba survivors, preserves endangered heritage via ALDAR and Studio Mozayan in al-Souk’s alleys. She practices “spatial resistance” against settler-colonial erasure, reclaiming homes, memory, and identity through community-led rehabilitation.