The Keffiyeh as Accessory; the Palestinian as Décor

In recent years, the Palestinian cause has shifted from a living, liberatory struggle into a symbolic “idea” easily circulated, easily appropriated, and adaptable to every context: political, humanitarian, even performative. For many, Palestine is no longer a genuine goal to fight for, but rather a means of signaling moral virtue or polishing one’s image. The keffiyeh, for example, is no longer merely a symbol of resistance; it has become an accessory worn at parties, protests, and TV appearances, sometimes draped over the shoulders of people who have never bothered to listen to a single Palestinian voice.

This text is not meant to generalize or to disregard the genuine efforts and sincere voices that continue to act with integrity and courage. There are many individuals, artists, and initiatives whose presence and impact are deeply valued. Yet, alongside that recognition, there exists a real sense of anger and disappointment that must also be voiced because the repeated patterns of symbolic appropriation, shallow representation, and instrumentalization of our struggle as decorative discourse are part of the lived Palestinian experience today. This uncomfortable layer is not an exception to the story; it is part of it, and it must be spoken about openly.

Palestinians, in this scene, have become a ready-made image expected to embody the victim: silent or emotional, but always within the parameters set by the audience, not by themselves. They are not allowed to show their contradictions, their complexity, or their difference. If they expresse something that doesn’t align with the dominant narrative, or if they appear in a European country trying to build a new life, they are met with suspicion or disdain. Their very existence becomes inconvenient, because it threatens the flattened image others prefer them to stay within.

Many conferences and cultural events in the West and even in the Arab world make sure to include “a Palestinian” in the picture, but only as a symbolic ornament. They are invited to sit on the panel or give a brief statement, merely so that organizers can say that “a Palestinian was present,” that “space was given,” though there is rarely any genuine intention to listen, engage, or allow change. The Palestinian, here, is reduced to a decorative sign, a necessary detail to complete the image, nothing more.

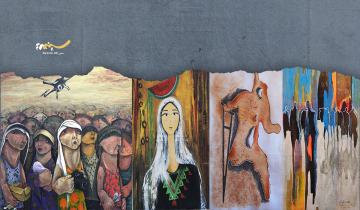

Worse still, they are often invited only when their presence can yield financial benefit, or when it grants a project a veneer of “authenticity” that makes it more marketable. Palestinian art in all its forms, from poetry to visual art to crafts, is increasingly exploited as a fashionable commodity, a profitable “trend.” “Palestinian art” is sold and branded as a label, while real Palestinian artists are excluded from funding, invitations, and exhibitions.

How many times have we seen self-proclaimed “defenders” of Palestine dominate social media platforms raising funds, speaking in our name, performing justice only to ignore, exclude, or tokenize actual Palestinians when they meet them in France, Germany, or Lebanon? “We had a Palestinian on the panel,” they’ll say, or “We gave them a short intervention,” as if that alone fulfills the duty of inclusion regardless of what the Palestinian actually said, or wanted, or felt.

In the Arab world, this dynamic takes on an even harsher form. Palestinians are expected to be endlessly grateful for any support they receive, never to express criticism, pain, or even need. If they do, they are instantly attacked: “You people never say thank you,” “We’ve always helped you and it’s never enough,” “You ask for too much” as if Palestinians were a burden on others, rather than a people being slaughtered daily before everyone’s eyes. Solidarity turns into a tool of humiliation, constantly thrown back in their faces, instead of a natural moral stance toward an oppressed people.

We’ve seen academics publish books about Palestine without meeting a single Palestinian. Artists use the Palestinian flag in their work while denying Palestinian artists access to their exhibitions. Institutions organize “Support Gaza” conferences, yet deliberately avoid inviting Palestinians who don’t fit their liberal, Western, or “progressive” image.

Worst of all, some of these actors stand with Palestine only when it’s safe and rewarding to do so, when the slogan is trending, or when solidarity can serve as a pass into cultural or political circles. But once solidarity becomes costly, once the Palestinian speaks “off-script,” they are quickly pushed out of the frame.

And so, we Palestinians have been turned into symbols, props. We are allowed to speak only if our words soothe the audience. We are used to beautify their positions, to applaud when they say: “Free Palestine.” But the moment we open our mouths to say, “I am here, I have a story, a different opinion, a fatigue of my own,” our voice no longer fits the script.

Mahdi Baraghithi

(b. 1991, Ramallah, Palestine) is a visual artist working in performance, installation, and collage, exploring masculinity and the male body in Palestinian society through found images and readymades. He holds an MFA from ENSA Bourges (2018), a BA from International Academy of Arts Palestine (2015), and a diploma from Palestine Film Institute (2010). Solo shows include Zalameh (Zawyeh Gallery, 2019) and Dominance Over the Grass (A.M. Qattan Foundation, 2022). Current residencies: Cité Internationale des Arts, Artagon Pantin, and La Box Gallery (2024).