The Mukhtar and I: A Day with My Grandfather in the Old City

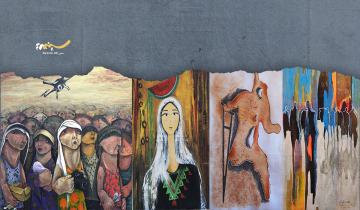

If someone in a pub asked me to describe my family’s story in one sentence I would say: “Exile and starting over; exile and starting over; and exile and starting over.” I would probably add a clarification that I did not repeat those words three times because I had too many beers. But my family’s experience of multiple exiles, from Katamon to East Jerusalem to Beirut to New York, is not unique; it is but one of the many sad episodes of “being Palestinian.” Our stories of exile, displacement, and injustice will live on, as will all our beautiful memories of our homeland. This is one such story I wrote for my Palestinian American children to share one day with their children and their children’s children.

The morning my grandfather and I took a walk together in the Old City, he turned to me and said: “Today you get to spend the day helping Sido (grandfather) at the qahwe (café).”

The year was 1966, and I was barely eleven years old. We were living in Beirut. Often during the summertime, my mother would take me, together with my younger brother and my sister, to visit Tata (grandmother) and Sido in the Old City of Jerusalem. Sido Issa Toubbeh –a stern-looking, tarboosh-wearing (fez-wearing), za‘oot-sniffing (snuff), nargileh-puffing, mustachioed man– was the Mukhtar (literally, the chosen), the head of the Eastern Orthodox Christian Arab community in Jerusalem.

As a young boy, I dreaded my stay at my grandparents’ residence. I was petrified by the sight of all the ugly, bearded monks with foot-long keys who occupied the Greek Orthodox Convent, where my grandparents lived after their forced exile from their home in Qatamon. The intoxicating smell of incense and burning candles, the spooky, narrow, cobble-stoned alleyways of the convent grounds, the robed priests roaming around in the dark –all contributed to a feeling of anxiety and discomfort I could do without. But on that morning, which was unlike any other morning, a sense of joy swept over me.

My memories of that day are as vivid and as bright as a silver coin in the sun. Sido and I, hand in hand, walked through the streets of Jerusalem, stopping every few paces to greet people he knew and those who knew of him. Along the way we passed the market, a bustling collection of colorful fruit and vegetable vendors. I instantly felt the flow of musical energy emanating from the place and its people. Music was simply all around: from the unforgettable melodic chanting of the muezzin’s call to prayer (often juxtaposed against the ringing of church bells) to fruit and vegetable vendors in the market singing praises about pickling cucumbers (as small as babies’ fingers) or prickly pears (so delicious they melt in your mouth); from the cheerful foot-thumping sounds of children practicing dabke dancing to the powerful emotional songs of Um Koulthoum blasting from transistor radios on window sills. To this day I am still able to close my eyes and transport myself back to the Jerusalem days. I am still able to smell the delicious food sold by street vendors, especially the wonderfully rich and evocative scent of roasted chestnuts and, of course, the sumptuous sweets drenched in qater (sugar syrup) sold at Zalatimo’s; I am still able to see the old street photographer with the wooden camera whose head often disappeared underneath a black cloth; still able to touch the olive oil soap stacked in the long cylindrical towers at the corner store.

But the one thing that intrigued me most of all, the one person that had a profound influence on me, was the juice vendor who walked with his body leaning forward and his Bordeaux fez with the black tassels tipped back. Not only did he carry a big tank filled with sous, jellab, and lemonade on his back as he traveled by foot from neighborhood to neighborhood, but he was a percussionist of the highest degree. I was fascinated by how he announced his arrival, and mesmerized by how he played beautiful, intricate rhythmic patterns, using brass cups and saucers, to entertain customers and alert them of his presence; rhythms very similar to the ones belly dancers moved their hips to in Beirut restaurants. From that moment on I was hooked. I would sit on the sidewalk with my eyes fixed on the juice vendor’s hands so I could learn his art. Back at the house later on, to my grandmother’s horror, I would practice the same rhythms using her china, which produced disastrous results and, it goes without saying, a spanking.

Adjacent to Jaffa Gate was my grandfather’s long-established café. Known to family and friends as al-Mahal (the place) and to others as Qahwet al-Mukhtar, the café was a renowned Jerusalem institution frequented in its heyday by the Palestinian literati, nicknamed al-sa‘aleek (the vagabonds). Poets, musicians, historians, storytellers, folks who wanted to be seen in their company, young Palestinians who aspired to be like them, or simply those who just wanted to listen to the exchange of ideas taking place, gathered at al-Mukhtar’s café.

The café was buzzing with people when my grandfather and I arrived from the market. For the next hour or so Sido attended to the business of recording births, deaths, and marriages in his oversized leather book, giving advice in between, and stamping official documents that required his seal. When he was done, he signaled to me with his walking stick to follow him to the café backyard, a large paved area with rows of plants on each side, a round tiled fountain in the middle surrounded by tables and chairs, and a massive cage that housed chickens and over a hundred pigeons.

As we sat in the sun and snacked on watermelon and Nabulsiyyeh cheese, he told me funny stories and answered the many questions I had stored up over the years. His answers to silly questions like “Why do you wear a tarboosh (fez)?” and “What’s that stuff you sniff and makes you sneeze all the time?” and more serious ones like “Why did you leave Qatamon?” and “Why did you not fight the Yahood (the Jews) when they took your home?” kept me enthralled the whole afternoon. He told me about the bombing that demolished the Samiramis hotel down the road from their house in Qatamon and how the blast that Menachem Begin masterminded at the King David Hotel, close to my Uncle Michel’s office, instilled fear in the community and was the catalyst that drove many Qatamonians to flee their homes. I cried when he told me the story of the massacre that took place at the village of Deir Yassin. A quick change of subject to the art of pigeon flying restored my smile. And before we headed back home, he gave me an impressive demonstration by releasing all the pigeons and showing me how to fly them in a circle and then guide them back to their cage; all with only the help of a black piece of cloth tied to the end of a long stick. What he failed to tell me was that this exercise is done to attract other flying pigeons to the flock and ultimately back to the cage so that uncle Mitri could later serve them to the customers.

Back at the house that evening, while my grandfather rested his feet on a chair in the living room, Tata asked me to run over to the neighbor’s to borrow a bowl of rice. “What’s going down at beit al-Mukhtar (the Mukhtar’s house)?” asked the neighbor. I shrugged. My guess was that he told another in the neighborhood, and another told another, and in no time more than twenty-five or so family and friends descended on my grandparents’ house, which sent my grandmother (and a dozen or so female helpers) scrambling to the kitchen to prepare food for the guests. The feast and the festive atmosphere that ensued were like nothing I’d encountered before. Suddenly musical instruments appeared from nowhere, and poetry became the flavor of the day. While the men sang and played music in the living room, the women danced in the kitchen, and the children shuttled back and forth between the two. In between solo improvisations on the ‘oud (a fretless lute), the qanun (a zither-like plucked instrument), and the nay (a reed flute), that brought sighs of appreciation, the singer sang soulful mawwals (vocal improvisations in dialect) and made up new lyrics to familiar tunes. I recognized many of the rhythms the juice vendor played, and I was encouraged to join the musicians on the riqq (tambourine). The fun was interrupted when Tata ordered everyone to the dining room table. And what a table that was! There were keftas and kababs, hashwet jaaj (chicken with rice and pine nuts), and koosa mahshi (stuffed zucchini), and mezze plates as far as the eye could see: Hummus (chickpea dip), baba ghannouj (eggplant dip), stuffed vine leaves, glistening black olives, braided white cheese, glossy vegetables, plump nuts, and lush juicy fruits. It was like magic: Where did it all come from? I wondered.

After dinner, we all retired to the living room, and the music resumed. This time the men and women danced together to the soothing and hypnotic compositions of Zakaria Ahmad and Sayyid Darweesh, Mohammad Abd el-Wahab and Fareed el-Atrash. And I, naturally exhausted by the events of the day, fell asleep on my grandfather’s lap.

Early the next morning, a crowd of family and friends lined up at the Convent entrance to bid us farewell. We got into the service (taxi) that drove us to Amman and from there back home to Beirut. From the car window I waved goodbye to my teary-eyed Tata and Sido and yelled kalimera to the bearded monk with foot-long keys.

That was the last time I saw my grandparents; the last time I saw Jerusalem.

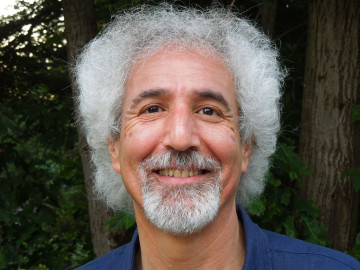

Michel S. Moushabeck

A writer, editor, translator, publisher, and musician of Palestinian descent. He founded Interlink Publishing, a Massachusetts-based independent house with 40 years of history. He has authored several books and regularly contributes to outlets like Truthout.org and the Massachusetts Review, recently guest-editing their “A View from Gaza” issue. He shares book reviews on Instagram on @ReadPalestine. He has been shortlisted for and awarded several prizes and awards. He serves on the board of directors of Media Education Foundation, the Interlink Foundation, and on the board of trustees of the International Prize for Arabic Fiction (IPAF).