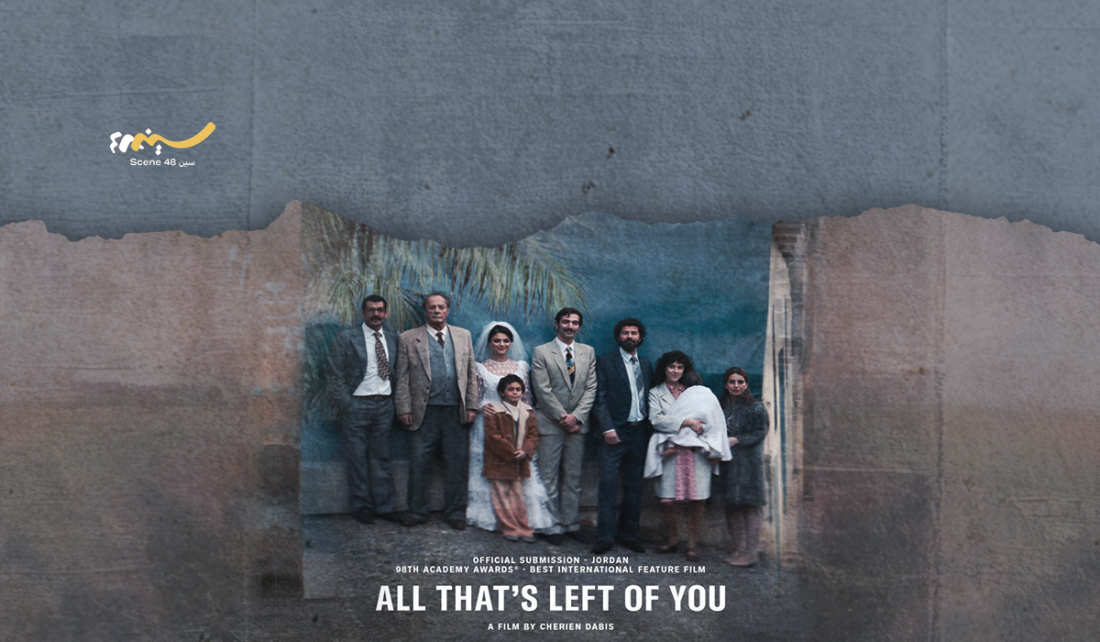

All That’s Left of You by Cherien Dabis, a Film with a Collective Memory Stature*

*Originally published in Arabic on Al-Quds Al-Arabi on 12 November 2025. Translated and published here with permission from author.

There are excellent films in Palestinian cinema, few but they do exist. The modest nature of Palestinian film production in general highlights the excellence of these few films even more., Some of these few special films, however, do not need the modesty of the general public to showcase their full excellence, which makes them transcend the Palestinian ceiling and qualify to stand alongside other cinematic excellences in the world. Cherien Dabis latest film, All That’s Left of You, fits into this approach as one of the films I have seen this year from around the world that combines high quality with entertainment and awareness.

Its Palestinian theme is not essential to this description; if all its elements had been replaced with another country instead of Palestine in its story, it would not have lost any of its cinematic and narrative excellence. Its tight writing, combined with the cinematography and editing, adds value to the film, making it a landmark that I believe will increase in value over time in the history of Palestinian cinema. Today, we are only at the beginning of our understanding of a film that, regardless of its Palestinian identity, is worthy of being a landmark in the current cinema of the Global South, auteur cinema in Europe, and independent cinema in the United States.

After Dabis’ first two feature films, Amreeka (2009) and May in the Summer (2013), which were among a large number of modest examples in Palestinian cinema, the director carved out an upward trajectory for herself in American television series production, moving away for more than ten years before returning with her third feature film, which came to be an important milestone in her career. Her experience directing series with titles that have made their mark in the United States (including Empire, Ozark, Ramy, Only Murders in the Building, and others), made this exceptional experience for a Palestinian not only a path to technical excellence in directing and editing, but also to excellence in cinematic storytelling. Here we have a film with a collective story, centering around a minor individual and family detail that becomes fundamental in giving the collective and historical context a tangible meaning: a detail that quickly grows beyond its initial marginality to take center stage, forming the cinematic plot. Dabis’ long hiatus from Palestinian filmmaking was necessary to break with her first two films and bring to this cinema one of the few best films in its history.

All That’s Left of You (Sundance, Karlovy Vary, and other festivals), which Jordan nominated to represent it at the Oscars, is a Palestinian epic spanning three generations, from the Nakba (Jaffa 1948) to pre-genocide (Jaffa-Tel Aviv 2022), passing through intermittent stages in the biography of one family (a camp in the West Bank, 1978 and 1988). In the first five minutes, we see grandmother Hanan addressing the camera, saying that she wants to tell the story of her martyred son, but before that, in order for her audience to understand, she must tell the story from the beginning: the story of the grandfather who was displaced from Jaffa. The listener here appears to be the viewer, but later, at the end of the film, in one of the most powerful dialogues in Palestinian cinema, we realize that the listener is an Israeli to whom the family donated the organs of their martyred son, along with others. This was the opening of the film, saying explicitly and directly to the viewer that in order to fully understand any individual story from Palestine, one must understand the collective story, the tragedy, the epic.

This introduction justifies, narratively, the inclusion of the family’s individual story within the broader context of the Palestinian people as a whole. The film, which is relatively long at nearly two and a half hours, depicts a family displaced from their home in Jaffa to a camp in the West Bank. The daily life of this family and their fears and concerns, all of which were an essential historical context for understanding the detailed story that moved from the margins to the center of the film, namely the killing of the son in a demonstration by occupation forces, followed by the parents’ attempts to transfer him to a hospital for treatment, available only in Tel Aviv. There, they face an ethical dilemma about donating his organs, after a previous harsh family experience in which they needed donor organs that they could not find. The martyr’s organs are finally donated, mostly to Palestinians, and then the confrontation came years later, in that dialogue with an Israeli who carries the heart of the Palestinian son.

From time to time, we see gratuitous humanism in Palestinian cinema, which makes the Palestinian character a pitiful figure, exaggerating his/her artificial and vulgar humanity in a certain situation, particularly in front of an Israeli, in order to elicit sympathy in response to excessive and unconvincing humanity. This image is so prevalent in Palestinian films that this twist in the story almost suggests such begging. However, the film, which used excessive humanity as a starting point (the humane behavior of a Palestinian family whose son was killed by a soldier’s bullet, in donating to patients in an Israeli hospital), ended up exposing the absurdity of this begging for humanity from the colonizer as exemplified in the organ donation. If the father, Salim, insisted that the recipients know that these organs belonged to a Palestinian killed by a soldier’s bullet, perhaps that would prevent them from becoming soldiers, perhaps that would protect Palestinian lives, and then the fact that most of the beneficiaries were originally Palestinian patients. The Israeli who carries the son’s heart, in the same intelligent dialogue, when she tries to explain to him the story of the family and, behind it, the story of the people, saying that the heart had Palestinian beats, he replies that the heart is now in an Israeli body, adding that his not serving in the army was, after all, for medical reasons.

The film thus empties humanity of its usual meaning, rendering it futile and pointless, even in attempts to demonstrate the moral superiority of the colonized over their colonizers in the most extreme cases, which here is the donation of the murdered son’s heart. The colonizer who takes the heart responds in a way that confirms the futility of any human excess on the part of the colonized. Therefore, it is one of the most daring dialogues in Palestinian cinema, albeit with few words, but the entire film is an epic context that surrounds it and paves the way for it.

The film is a Palestinian epic spanning from the Nakba to the present day, conveying the story of an entire people through a family saga spanning three generations, condensed into a single pivotal event in which collective tragedy collides with individual tragedy. This cinematic technique says the Nakba is ongoing, both technically and narratively, as the transition between times is fluid, barely noticeable to the viewer. It is sudden: one door closes and another opens; an image of a face turns into an image of the same face decades later, with the continuity of the sound suggesting that the situation was the same and that the event was one but extended. The voice connects the images to each other, and thus the times to each other, and thus the detailed tragedies, marginal throughout the history of this people, to the great tragedy of the present.

All That’s Left of You is the best cinematic representation of Elias Khoury’s assertion, which he theorized in literature, criticism and thought: the Nakba is ongoing. It is not a finished event, but a continuous context of detailed events, just as the martyrdom of the son and the ensuing continuity of the tragedy were. Even this detail, the martyrdom, was the beginning of a series of family tragedies that did not end even after decades, culminating in the parents’ visit as tourists to Jaffa on Canadian passports.

There are many scenes in which the camera takes the place of the distant observer, the expectant, anxious viewer, scenes from behind curtains or windows, from the end of the hall or from another hall. It is as if the scenes are wide shots from memory, fragmented, distant, as if trying to grasp the surroundings, trying to gather as many details as possible.

In this and other ways, the film is closer to being a collective visual memory for Palestinians. A simple and beautiful scene of a wedding in a camp courtyard suggests this, as does the boy’s participation in the demonstration, the arguments between the three generations, the soldiers’ humiliation of the father in front of his son, the parents in an Israeli hospital, and other scenes that Palestinian cinema has further cemented in the memory of this people, but here, they were technically and artistically superior. This is what led me to refer to the different areas at the intersection of which the film lies: cinema of the Global South, European auteur cinema, and American independent cinema. This film deserves to be present in all three of these spheres, and due to its human nature, narrative awareness and technical quality, it holds a special and high status in each of these paths in contemporary cinema paths. This is a Palestinian privilege.

Saleem Albeik

A Palestinian novelist, film critic, and researcher in Palestinian cinema based in Paris, founded and edits Roman Cultural. He contributes weekly to Al-Quds Al-Arabi. His novels include Ain Al-Deek (2022), Scenario (2019), and Two Tickets to Safouria (2017); his latest, A History of Palestinian Cinema: The Limitation of Spaces and Characters, was published by the Institute for Palestine Studies in 2025.